There is no room for “us/them” in the battle against COVID-19. There is only “we.”–Bernice L. Hausman and Heidi Y. Lawrence

In times of danger, it’s natural for us to want to protect and defend our families and loved ones. COVID-19 constitutes a serious threat. Think of the human body when it is being attacked. Heart rate increases, pumping additional blood to the muscles and brain where it is needed. Pulse and blood pressure go up, breathing quickens; vital systems are alert and ready to react. But once the acute danger has subsided, the body returns to a calmer, balanced state. When this heightened condition of readiness, referred to as the fight/flight response, locks in and becomes normal, bad things begin to happen, like chronic high blood pressure, vascular disease and anxiety disorders.

At the level of human society, we find similar dynamics. The ability to defend oneself and pursue self-interest is fundamental to democratic and free market models. But balance is necessary for the larger system to function well and stay healthy. Local needs and the needs of larger social groupings at the state, national and international levels need to inform and complement each other. Without balance, we risk distortions in the distribution of benefits and power that eventually undermine the system’s viability. Fighting an infectious disease presents an even greater challenge, since our individual health and well-being depends so heavily on the health of others. This means sometimes choosing global actions over local needs, never an easy choice. This is especially true when it involves sacrifice, and even more difficult if parties don’t genuinely identify or even much care for each other.

We know from prior pandemics just how devastating the effects of highly infectious disease can be. A century ago, the Spanish flu infected more than 500 million people, killing 10% to 20% of them. While it is tempting to invoke comparisons to war, this analogy misses the essential biological nature of the threat. Unlike wars which are won or lost against an adversary with strategy, guile and acts of daring, in this case, we need to work with the enemy, respecting and adapting together, drawing on the same basis of scientific laws and constraints. Rather than pushing us apart, this threat pulls us together, a consequence viewed by some as a bit of a gift. Just as many families anecdotally report that sheltering in place has given them precious time together, the virus can also be seen as a learning opportunity for humankind, a chance to practice global cooperation in preparation for even worse global disasters that are likely to occur in the future. Yuval Noah Harari, author of Sapiens, flips the war analogy on its head in a recent Financial Times article, “Just as countries nationalize key industries during a war, the human war against coronavirus may require us to “humanize” the crucial production lines”.

By humanize, he means citizens of all the countries around the world need to be on the same side in order to attain victory.

Tragedy Of The Commons?

One way to think about this particular dilemma is as a breakdown in cooperative behaviour due to a set of conditions known as the Tragedy of the Commons. In this scenario, parties over-consume shared resources out of ignorance or the assumption that others will, so they had better do it first. It is me-first thinking, and once the cycle is initiated, it is difficult to stop. Since we can’t control what other countries are doing to prevent transmission of the virus locally, we can at least fortify efforts here. In doing this, countries and smaller social entities like states or cities, end up fighting over scarce supplies and resources like medical specialists. The unintended consequence of this becomes a shortage of highly valued items for everyone. Appropriate masks and respirators (and toilet paper) became scarce early in the pandemic, leading to hoarding, and shortages in locations where they were most needed.

The most direct way to get everyone to share the Commons (materials, supplies, labs, knowledge) fairly is to impose orders and penalties, but of course, this can meet with resistance and has other negative side effects pertaining to control and freedom. Political scientist and Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom solved this conundrum by inserting a set of operating rules that all involved need to adopt. There are eight rules in total, things like clearly defined boundaries, local autonomy and fast and fair conflict resolution, that allow the parties to successfully self-regulate

Or Zero-Sum Game?

Another explanation for a breakdown in cooperative efforts is what game theorists refer to as zero-sum thinking. The basic idea here is that resources are assumed to be fixed, and that for one party to be successful, the other parties must lose. For our city (or community or country) to conquer COVID, it is inevitable that others will not do quite as well; survival of the fittest. We saw this thinking in action in March when, according to German sources, Donald Trump attempted to buy a German company that had an early lead in the race to a vaccine, so that Americans would be first to receive a vaccine. The alternative, or antidote to zero sum is win-win thinking, where the pie that we are sharing can be expanded. In an overly connected world scenario, this is a much more helpful and adaptive assumption to carry.

And finally, we need to challenge the local versus global dichotomy itself; the notion of us versus them, whether referring to family, religion or country. The very notion of one group’s self-interest being at odds with others’ begins with creation of exclusive boundary lines. Humans are more alike than different; we share 99.9% of DNA (versus .1% of difference!), and our fates as individuals are becoming more tied every year to our ability to act collectively against threats that affect us all like viruses, pollution and climate change.

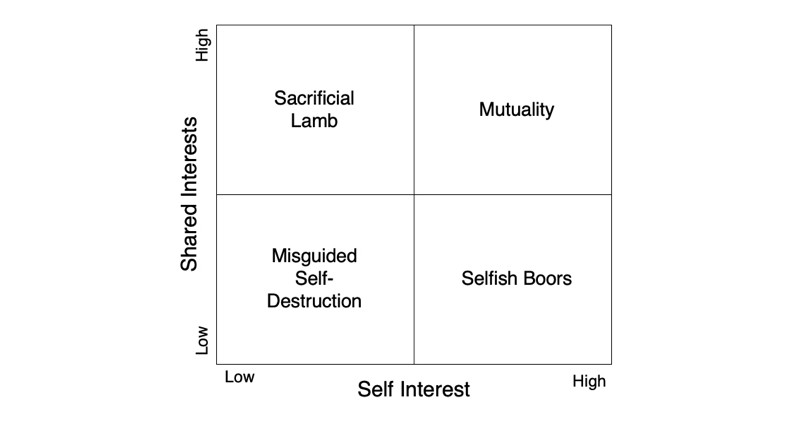

Modeling the Whose Interests Matter Dilemma

Mapping the two dimensions onto a 2 x 2 grid produces four possible scenarios. Upper left, Sacrificial Lamb is the case where one entity, be it an agency, city or nation, puts the greater, collective need ahead of its own. Think back three months when businesses shut down and people agreed to work from home and stop normal socializing, all in an effort to curb the spread of COVID across the country and around the world. These changes at the local level caused considerable short-term economic and social pain, but produced meaningful gains. It is doubtful that restrictions such as these can be sustained for the long haul. But they did occur. At the level of nations, we have seen a wide range of readiness to shut systems down, with some countries imposing extreme restrictions like Italy and China and others, like Sweden, choosing to let people set their own limits.

Lower right, Selfish Boors, is the case where it is all about us, and as long as we are okay, then others can look after themselves. Globally, we see the potential for this, as rich and poor nations have different capacities to respond to the virus. The recent US withdrawal of funding from the World Health Organization in the midst of this pandemic is an example of choosing to not identify with the larger global community and spend exclusively on solving the problem at home

Figure 1. Modeling the Whose Self Interest Dilemma

Upper right, Mutuality, is the happy confluence of needs between parties which operate at different sizes and levels; situations where what is best for the larger entity is also in the smaller one’s self-interest. In the case of COVID, fortunately, this seems to be happening often. Research for a cure is costly and risky; and we are all better off sharing resources, lessons and solutions. We are seeing many examples of this between countries, research labs and pharmaceutical companies sharing vital proprietary information in the search for vaccines and cures.

And finally, in the lower left, we have Misguided Self-Destruction, the least well informed and successful option of the lot. Ignoring scientific advice, those in this category carry on in the hopes that the virus will miraculously inflict little to no damage to them. Many countries—or their leaders– fall here, sadly, including the likes of Russia, parts of the US and Brazil. Sweden went into its strategy with eyes wide open, hoping to quickly “immunize the herd” and move on. Their chief epidemiologist, Anders Tegnel, has recently recanted his earlier position, saying he was essentially wrong in recommending the approach, as the country puts catch-up efforts in place to limit damage already done.

Making the Case That the Local Versus Shared Interests Dilemma Is Politicians’ #1 Priority

For each of the 10 COVID-19 dilemmas, we will be examining key drivers that should be of concern for leaders. We are NOT saying this is the most pressing of the 10 dilemmas. Rather, we are exploring factors that need to be considered.

Here are three key reasons this should be the top priority of governments as they strive for balance while combatting COVID-19:

1. Recognize increasing interdependence – Humans have always needed others to survive, but the degree of planetary interdependence has reached new heights. Areas of shared need and cooperation range from supply chains, technology-exchange, food, education, economies, travel and tourism.

2. Separation is illusory – Increasingly, no one is safe unless everyone is safe. Viruses don’t recognize geography or nationality. As the world becomes ever smaller and more interconnected, global health determines local health, and isolation from the global community is not a viable option.

3. Vast inequalities abound – Gaps between rich and poor, be it individuals, regions or nations, have risen to dangerous levels. We know that COVD-19 is not experienced equally across the spectrum, with the poor being impacted far more. Some will require assistance to curb spread of the virus.

Insights and Implications

1. Think win-win: In the darkest moments, it is understandable to worry about worst-case outcomes and to do whatever is needed to solve our part of the problem. But this can be unhelpful and a trap if you continue to think in this way after the crisis has abated.

Recommendation: Remember we are all connected, now more so than ever. A sustainable victory over COVID include ameliorating the problem around the globe. Keep an open mind. Challenge negative and limiting assumptions. See the points of interdependency and be motivated by these.

2. Lead with empathy: COVID is a global problem that will need to be solved everywhere. It will take persistence, collaboration and assistance from countries with more resources and medical professionals who can help out.

Recommendation: Put yourself into the place of others (less fortunate citizens, other nations…) when developing plans. Follow the axioms of the Design Thinking folks whose methodology begins with empathy and understanding, continues with embracing constraints, and ends with experiments and adjusting until the problem is solved.

3. Be systems thinkers: Systems thinking is concerned with relationships and dynamics rather than individual pieces and positions. COVID-19 is complex, with thousands of moving parts that need to be considered. Many of these are outside of your direct control, and new, confounding challenges like the recent killing of George Floyd and the mass public rallies around the world that have followed, will continue to happen.

Recommendation: Think about all the parts and dynamics as elements of a complex system which needs to be constantly monitored. Anticipate short- and long-term effects influencing each other and be prepared to make adjustments.